Quicklinks

Quicklinks

The current disruptions to global supply chains raise questions about how the logistics of the future could become more resilient, collaborative, efficient, and also environmentally friendly. Will marine diesel be replaced by ammonia? Would it be better to manufacture spare parts locally with 3D printers instead of transporting them halfway around the world? What tasks will artificial intelligence take away from us? These and similar topics of the future will be addressed by the HHLA Talk with Professor Dr. Carlos Jahn. He is head of the Institute for Maritime Logistics at the Technical University of Hamburg and is also head of the Fraunhofer Center for Maritime Logistics and Services in Hamburg-Harburg.

What is AI all about, how does HHLA benefit from this technology and what are the advantages and disadvantages?

Dive into AI in logisticsToday, we welcome one of the most distinguished German scientists in the maritime industry to HHLA Talk. Professor Carlos Jahn heads the Institute of Maritime Logistics at Hamburg University of Technology as well as the Fraunhofer Center for Maritime Logistics and Services in Hamburg-Harburg. Welcome!

Yes, thank you. I am very happy to be here in this impressive HHLA Media Hub.

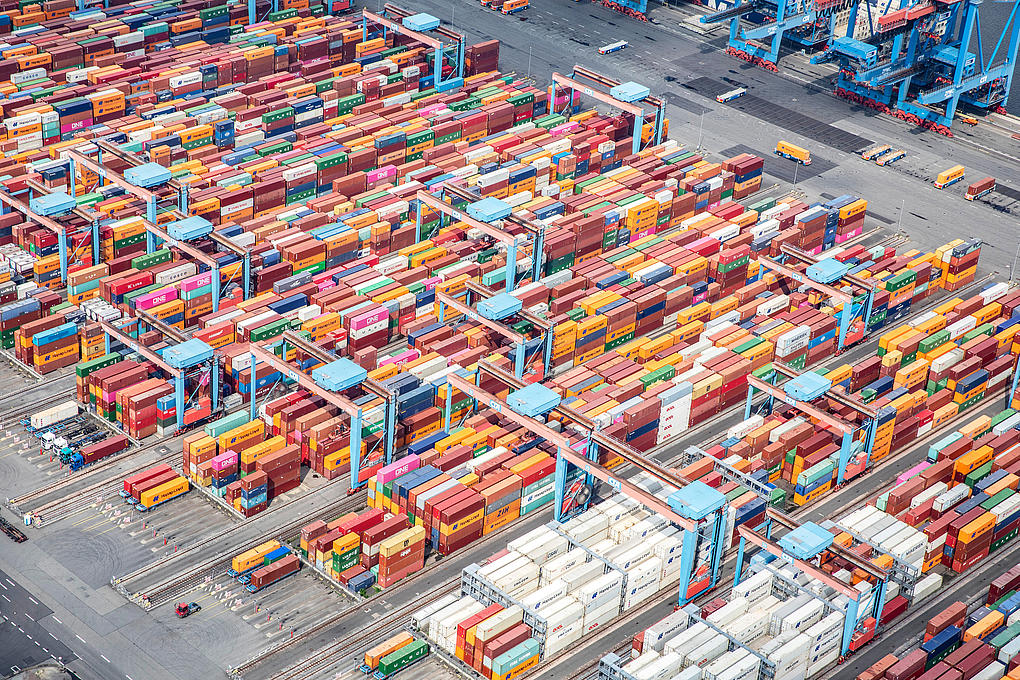

At the moment, ships, ports and logistics are – one might almost say unfortunately – a major topic in the media. We are experiencing a widespread disruption of global supply chains at an unprecedented level. Did the effects of the coronavirus pandemic come as a major surprise, or might there be systemic or structural problems in globalised logistics?

Well, that’s an interesting question. I don’t think that this is a systematic failure or that there are systemic weaknesses in the global supply chains. Basically, one must say that maritime logistics in particular is a highly efficient interlocking system. It provides transport options that are affordable as well as eco-friendly and reliable. And the fact that the coronavirus crisis is now leading to smaller disruptions with closed production plants and closed ports actually shows that the system is very efficient and does not waste resources. On the other hand, it would be astonishing if everything were running as usual despite these setbacks in production and handling. That would mean that the system is designed too stringently, which is not the case. Cooperation is the foundation of maritime logistics. Shipping lines, ports, logistics and service providers have naturally been working together for years; otherwise, the chains would not work nearly as efficiently. Only the data-sharing facet is new. And more willingness to cooperate would help here as well.

Without cooperation, logistics chains would collapse. We also see now that most problems can be solved with improvisation and cooperation, even in difficult situations such as the current one. Perhaps we might talk about technical innovations. There could also be innovations that help simplify complicated supply chains. I’m thinking, for example, of 3D printers for the fast delivery of important replacement parts. Do you see where innovations such as 3D printing might alleviate supply chains at certain points?

3D printing is without a doubt a fantastic technology, especially when you realise that it’s not just plastic that can be printed. By now, we can even manufacture metal parts whose physical properties are comparable or even superior to their conventional counterparts. There are definite possibilities in lightweight construction. However, I think that only supply chains in niche segments will be affected by this. People often talk about replacement parts. It’s intriguing to say you can make replacement parts on site. The challenge, of course, is to implement this across the board. For one thing, unit costs are very high for 3D printing. This means parts become a lot more expensive than industrially mass-produced parts. Then there is also the question of warranties for technical parts that might be printed anywhere in the world. Who takes responsibility for making sure the parts conform to safety standards? I think we still have a long way to go before we can build chains that enable decentralised printing anywhere in the world, to the extent that supply chains are significantly affected.

Semiconductors, which are in short supply everywhere at the moment, can probably not be printed like this yet. But maybe 3D printing does help eliminate very specific bottlenecks. Another question about something that might have an impact: There are a lot of so-called zero-energy devices which are now smaller than they were. They’re important for the transportation chain because they continuously send data, for example. Do you see an opportunity here to guarantee the consistency of transports? If, for example, a container were continuously broadcasting its location, might this lead to better management of delays?

You are alluding to the topic of smart containers. Let’s say I have a device on the container, ideally using zero energy. Naturally, it doesn’t use zero energy. It sends data, but it might take its energy from the movement of the container. It is fascinating to imagine this world where you always know where every container is, where it’s going and what condition it’s in. Not to mention the temperature, the movement and what jolts it might have absorbed. How is the humidity inside the container, and so on? The question arises: Imagine that the approximately 30 million containers worldwide were now equipped with this. How would you actually use this multitude of information to generate added value at various points of the logistics process? This is not so much a purely technological question as a question of logistical methodology. What do I do with the information? A ship comes along with 20,000 containers that send information every few seconds. And it’s not just one ship, but a great many ships. The flood of information is immense. And then, how can I actually add value if I know where every single container is? I think this world will await us in the future, because devices will become cheaper and more reliable, and we will be able to deal with more and more information. From that perspective, the vision is intriguing. However, we still have quite a way to go before it happens.

In the future, shippers will be able to safely keep track of their containers with the help of intelligent monitoring technology.

Everything you’re describing represents a flood of information and data. And I found your perspective very interesting just now. What limitations do you think this will come up against? Anything is possible, but ultimately there are always practical limitations. 30 years ago, we thought our offices would soon be paperless. That hasn’t happened yet.

The limitation certainly lies in getting use out of it. It’s fascinating to deal with large amounts of data. It is fascinating to develop algorithms, especially with artificial intelligence, to gain insights from this data. But it is another step to actually generate added value from this for practical use, and to consider how the information helps me. I can think of a lot of information that is fundamentally interesting, but which – even if I have it, and have it on time – actually has little or no impact on improving my chain. And figuring out how to filter it – which information is right? Who uses it? To whom do I make it available, and when? And how does it enter into subsequent processes? This presents a challenge and also a limitation. Something like this doesn’t develop overnight. It is a process, and thinking about such questions is a joint task for everyone involved in the logistics chain.

You often talk about synchronisation – that is, improved interlocking of supply chains. This also includes the collaborative exchange of freight data, for example. What would you say: Is this possibly in contradiction to the very strict data protection laws that exist in the EU? Or do the players find other solutions?

Of course I understand the data protection regulations and the need to protect data. On the other hand, I am also an optimist. I think that in the end, good solutions will prevail, as will the potential that data exchange provides for the synchronisation of processes. It’s not just about having less idle time. Having less idle time means that I might achieve the same handling performance in the ports with less space. With less equipment idle time, I can also manage the same performance with less equipment. This also means less resource use, less surface area, fewer emissions. And this is certainly persuasive. More and more examples demonstrate what synchronisation can achieve, and that the data protection challenge can also be managed.

Would the blockchain be a possibility, because data can also be stored anonymously in the blockchain? As far as I know, blockchain technology is not so strongly affected by these data protection issues. Do you have any examples, or do you know more about this?

The blockchain is, of course, a very interesting approach. It is a decentralised technology, of which there are several. I believe that the trend in the future will be to create decentralised solutions. Decentralised data storage, decentralised data exchange. I don’t think that data protection is the brake here. Instead, I think the brake is the understanding on the part of the various market participants, who are, after all, competing with one another. Here, they have to enter data into the systems that is also of use to others. Perhaps their own benefit isn’t apparent to them in the short term. I think that’s what’s holding things back at the moment.

So this is a cultural issue – that people have to learn to cooperate. Also, by giving – by releasing data – you can achieve an effect together that didn’t previously exist. I would now like to talk about a major – let’s call it an invention – that we at HHLA are involved in, together with the US developers of HyperloopTT. And that is the Hyperloop. What do you say to that? Would that really be an important invention? Perhaps also with a view to climate change, because this involves nearly carbon-free transport?

The technology is fascinating, without a doubt. The idea of being able to manage transport over long distances using little energy is, of course, a real thrill for the researcher. Especially when you see how close these activities are to becoming reality. Naturally, the question is how this can actually be translated into economical transportation. I think that’s the limitation here as well. Is it possible to create a completely new infrastructure, in addition to our existing infrastructure, that can compete with existing options in terms of its ability to transport cargo? With regard to price as well as logistical handling for certain niche transports. That’s how I understand HyperloopTT operates in the market – that it identifies certain niches where it makes sense. I also think this will be part of our future transport system. From my point of view today, it’s more of a niche product that can fill important niches. I see it as an addition to the transport system. I do not foresee a future where our world is equipped with Hyperloop routes and where rail, inland waterway ships, trucks and ships decline.

What we have just addressed is the carbon-free transport of goods, which is one of the most important issues of the future. Do you see a possibility there? Whether it be through technology, or perhaps new energy sources for powering ships, aircraft and other means of transport in a climate-neutral way?

Yes, of course, the technology is already there. It is possible to produce synthetic fuels that – if we obtain the energy for them sustainably – are actually green. So that is technologically possible. As with everything, the question is: Can this be implemented in our economic system? That is the big challenge, because at the moment these fuels are crazy expensive. It is not foreseeable that they will become very, very cheap in the near future, so that they could even compete in price with the existing fuel supply system. It will certainly take time to bring such fuels into widespread use.

But unfortunately, we don’t have that time. At this very moment – while we are conducting this interview – the big world climate conference is taking place in Glasgow. Everyone there is saying we don’t have that time. When I think of alternatives like ammonia, for example – that’s available, it’s already being used in the chemical industry. And because shipping simply needs alternatives, would ammonia, for example, be such an alternative? Or do you think that LNG – as another example – must continue to be legitimised as a bridging technology for another 10, 20 or 30 years?

I think that this conversion, this decarbonisation of shipping, the big buzzword, just needs more time. Of course there is ammonia, but if we were to flip the switch all at once now, we would need immense quantities, and they would have to be produced first. This in itself is questionable with the capacities we have – you can’t just increase them significantly at the push of a button. You also have to get them to the places where the ships need them, and create the corresponding refuelling systems. And of course, you have to have the appropriate ships to process this fuel. Ships are also large technical installations that are not built overnight. So it just takes time. Even if there is a certain pressure to push ahead with this decarbonisation, it is a process that takes years and is not possible overnight. But ammonia would certainly be a good alternative. LNG, which you mentioned, is accepted as a bridging technology. More and more, even large container ships are being built that use LNG in the interim. And of course, LNG is better than other fuels based on crude oil because the emissions are significantly lower. I don’t think it’s black or white. You can’t flip a switch to plus or minus, and suddenly everything is climate-neutral; it’s a process. And in this process, different fuels have a role to play. Ammonia, other synthetic fuels, LNG... These can help this noble goal of decarbonisation to be achieved in the future. But certainly not overnight.

Our topic is indeed the future. And when we talk about ammonia, when we talk about hydrogen, when we talk about “renewable energy”, we realise that in Germany, sun and wind are not necessarily available to the same extent as they are in other countries such as Morocco, Chile, Saudi Arabia or Australia. When you think about the fact that electricity prices in these countries are likely to fall, while they have been rising steadily in Germany for a long time – can you imagine that this surplus of solar and wind energy, which can also be converted into ammonia or hydrogen, will lead to a drastic shift in industrial production? And along with this, of course, complete restructuring of the international exchange of goods?

Yes, that’s an interesting question. From my limited perspective, I don’t see it that way for now. Of course, energy is an important cost factor in industrial production, but it is not the only factor. When I look at industries that produce highly complex products, energy is of course a factor. But the factor of proximity to the market is also important, as are the factors of the availability of labour and a supplier network. When I look at a modern factory today, it is more like a network that brings parts together. When complex products are created in such a high-performance logistics process, is it possible to simply relocate the whole thing on a large scale? To relocate it drastically to a region where there might be little apart from a lot of sand, just because the electricity there is cheaper? I can’t imagine that happening very quickly! For certain niche industries, that can certainly be a factor. But as an optimist, I also hope that our high electricity prices might be tamed again with the new technologies.

I also remembered that products like hydrogen or ammonia could be produced in countries like Chile – with a lot of wind energy – or Australia – with a lot of solar energy – and then potentially shipped. People are already deliberating about how expensive this kind of energy might become here. Do you think that the hydrogen industry or the ammonia industry in Australia and Chile, for example, have completely different prospects than they do here, where there are already similar projects off places such as Heligoland?

I think so, and that we will then import it. By the way, this is also one of the projects that we are currently working on. We are building a simulation model that can map and evaluate such global hydrogen logistics chains using various transport modes. This will one day be part of our energy mix, but we must not believe that solar power or wind power will then be free. Because the plants that capture this electricity – be it solar or wind – naturally cost money. It costs resources to build them and also to maintain them. We see this with the offshore plants. Or if you think about it: solar plants in the desert – they are not free! They are challenged by sandstorms, as the most prominent example, which does not make them free. The question is, what are the costs of usage? Plus the conversion to hydrogen, plus the transport. It’s not free, but it will definitely be part of our future green energy mix.

The fact is that Chinese or Asian companies from Japan, Taiwan and South Korea dominate production in many sectors, for example in the manufacture of semiconductors and solar panels. In addition, the majority of the world’s largest ports are still located in Asia, particularly in China, and intra-Asian trade is also becoming increasingly important. This means that Asia is becoming more powerful as a logistics player. What do you think: What will the trade routes look like in 20 or 30 years? Will Europe still play the rather dominant role that it does now? Or will things perhaps shift?

Looking 20 years into the future is of course not so easy. But you mentioned development. The Asian logistics processes are simply more dominant. The economies there are also growing very fast and the exchange of goods is increasing. We see that Europe is losing importance worldwide in terms of volume. Though what’s important are not only quantities, but WHAT is produced and exchanged. I think that Europe has a great opportunity to remain the dominant player, especially in the field of high-tech products. I also hope that the political framework conditions will remain as they are, and even be improved. This will allow us to maintain Europe’s innovative strength, which is fed by various sources such as the excellent education system. Even if not in terms of quantity, we are essentially leading in terms of the quality and innovation of our products. So I don’t see things so negatively. One reads exaggerations on this subject from time to time.

We have talked a lot about innovation and the future; they seem to involve an exchange of ideas. Which of the transport and logistics innovations that are not too important at the moment, but are becoming a bit apparent, might become a game changer in your opinion?

“Game changer” is a grand term. I don’t think logistics chains will change very dramatically. They have been pretty similar for centuries. Goods are brought to ports, loaded onto ships and transported. I think this basic principle is very, very stable.

So the ship won’t be replaced any time soon...

No, I don’t think so. What I foresee, for example, is the growth of artificial intelligence. This will change much in logistics and make a lot possible, such as improving decisions, to begin with. I can base decisions on even more data. And as a human, though I can no longer evaluate this volume of data alone, I can do it by using artificial intelligence. This means that decisions can not only be prepared, but also automated. Many trivial things that might have to be decided by humans today will be decided by artificial intelligence. What will this change for people? There will be fewer routine activities, boring things. Work that I would call work in the system will increase. That is, we will increasingly be there for exceptional situations where human creativity is unbeatable: for putting out fires, and for exceptional situations. And we will work on the system. It is clear that artificial intelligence is inherently stupid. It does what it is told. This is a great opportunity if we participate and design the rules according to which AI makes decisions. And not just in a void, but specifically for logistics. There are interesting perspectives here, because we can synchronise and improve logistics even more by using the possibilities of artificial intelligence. We can direct it very well and lead it in the right direction, towards more efficiency and more sustainability in logistics.

You are also involved in a research project on this subject, which only represents a very small part of artificial intelligence. But since you researched our terminals, I want to touch on it briefly. The subject was automated transport, and you looked at trucks. How would it increase productivity if they were automated? What did you find out?

Yes, the team mapped specific traffic scenarios in the port and created a simulation model that depicts traffic entirely with classic trucks, i.e. the current situation. And we also have the option of mapping autonomous trucks, which behave differently. Their driving speed as well as their stopping, parking and overall driving behaviour is quite simply different. Now we can analyse how the overall productivity of this transport system changes when it consists of 10, 20, 30, 100 percent autonomous trucks. What changes in the system? What would have to change in the infrastructure? What we find is that autonomous driving contributes to productivity. It does not lead to the system as a whole becoming slower because the trucks might drive more slowly; it leads to an increase in productivity. We can analyse this very precisely for individual areas, and we can also deduce from the findings what actually needs to be changed in the infrastructure. One thing is clear: we must change our infrastructure in order to optimise it for autonomous driving. There is great potential. However, these trucks are currently only available as prototypes and will not make up a large part of the fleet next year.

We have started such an initiative ourselves, the Hamburg TruckPilot project. So we’d be ready! If you say it would increase productivity, we hope autonomous driving will soon be more prevalent. There would hopefully be fewer accidents. Hamburg is a major hub for road traffic, with the A7, the A1 and so on. Do you think Hamburg can secure its function as a central Northern European logistics hub in the long term?

Yes, I’m certain Hamburg can. Of course, this isn’t a decision for individuals to make, but rather a social decision on how to develop a location. But with everything I see in terms of development and also in terms of people’s motivation, I think we would be ill-advised to want to give up our special position. It offers us many advantages, not least prosperity. But to return to sustainability, it also offers us the opportunity to make a huge contribution, because we have the technologies and the motivation to move forward.

In Hamburg, we also have the largest railway port in Europe, perhaps even in the world. We thus already rely on a very environmentally friendly mode of transport. This really brings us to the last question, which pertains to rail. Do you see a way to significantly increase the efficiency of rail transport if we want to put more goods on the rails, or do we simply have to build more new lines?

Certainly there are two parts to this. One is: you need more routes. Quite simply because, even with the best digitalisation, you cannot physically have two trains running on the same piece of track at the same time. Therefore, we need more infrastructure if we want to bring a lot more traffic onto the railways. On the other hand, you can draw even more potential from the existing system through digitalisation. Here I would like to once again address the problem of synchronisation. By exchanging information in advance, it must be possible to reduce certain idle and standing times in order to enable more traffic to move on the existing infrastructure. But if we want to make great leaps, we cannot avoid expanding the infrastructure. The goal and the result should really motivate us to move forward on this path.

Professor Jahn, you’ve provided us with a lot of interesting glimpses into the future. They essentially shed quite a positive light on Hamburg, on Germany, and on climate protection. We hope that many of them will come to fruition. Thanks very much!

Yes, thank you! It was lovely to be here and to share some thoughts with you.

We guarantee our customers both climate-neutral handling and climate-neutral transport of their goods and commodities from our terminal facilities in the Port of Hamburg to the European hinterland.